The Banking Divide For Taxi Access: Evidence From New York City

In this project we use multiple datasets to explore taxicab fare payments by neighborhood and examine how access to taxicab services is associated with use of conventional banking services.

Since 2008 yellow taxis have been able to process fare payments with credit cards, and credits cards are a growing share of total fare payments. However, the use of credit cards to pay for taxi fares varies widely across neighborhoods, and there are strong correlations between cash payments for taxi fares, cash payments for transit fares and the presence of unbanked or underbanked populations. In this paper we use multiple datasets to explore taxicab fare payments by neighborhood and examine how access to taxicab services is associated with use of conventional banking services.

Green Cab Origins

Green Cab Origins

Taxicabs are a critical aspect of the public transit system in New York City. The yellow cabs that are ubiquitous in Manhattan are as iconic as the city’s subway system, and in recent years green taxicabs were introduced by the city to improve taxi service in areas outside of the central business districts and airports. Approximately 500,000 taxi trips are taken daily, carrying about 800,000 passengers, and not including other livery firms such as Uber, Lyft or Carmel. Since 2008 yellow taxis have been able to process fare payments with credit cards, and credits cards are a growing share of total fare payments. However, the use of credit cards to pay for taxi fares varies widely across neighborhoods, and there are strong correlations between cash payments for taxi fares, cash payments for transit fares and the presence of unbanked or underbanked populations.

These issues are of concern for policymakers as approximately ten percent of households in the city are unbanked, and in some neighborhoods the share of unbanked households is over 50 percent. In this paper we use multiple datasets to explore taxicab fare payments by neighborhood and examine how access to taxicab services is associated with use of conventional banking services. There is a clear spatial dimension to the propensity of riders to pay cash, and we find that both immigrant status and being ‘unbanked’ are strong predictors of cash transactions for taxicabs. These results have implications for local regulations of the for-hire vehicle industry, particularly in the context of the rapid growth of services that require credit cards. Without some type of cash-based payment option taxi services will isolate certain neighborhoods. At the very least, existing and new providers of transit services must consider access to mainstream financial products as part of their equity analyses.

Overall there are observable differences for cash payments by taxi type, location, trip origin and trip destination. It is impossible to know what characteristics differ between a typical yellow cab passenger and a typical green cab passenger, but something leads green cab passengers to use cash far more often than yellow cab passengers. The results shown on the maps suggest that there is a spatial factor in play.

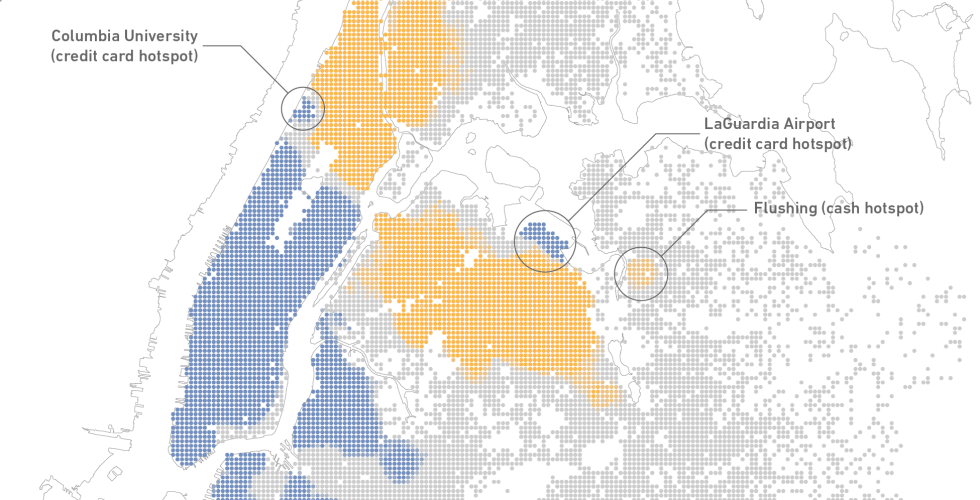

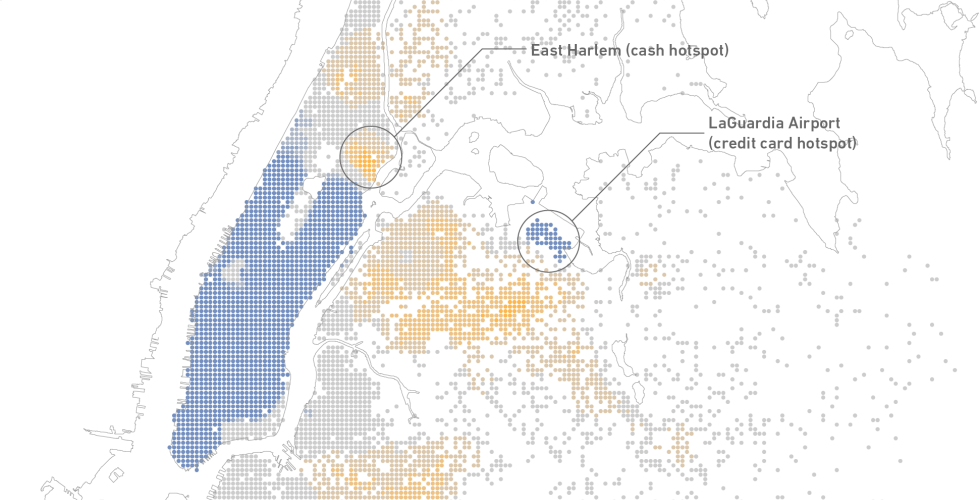

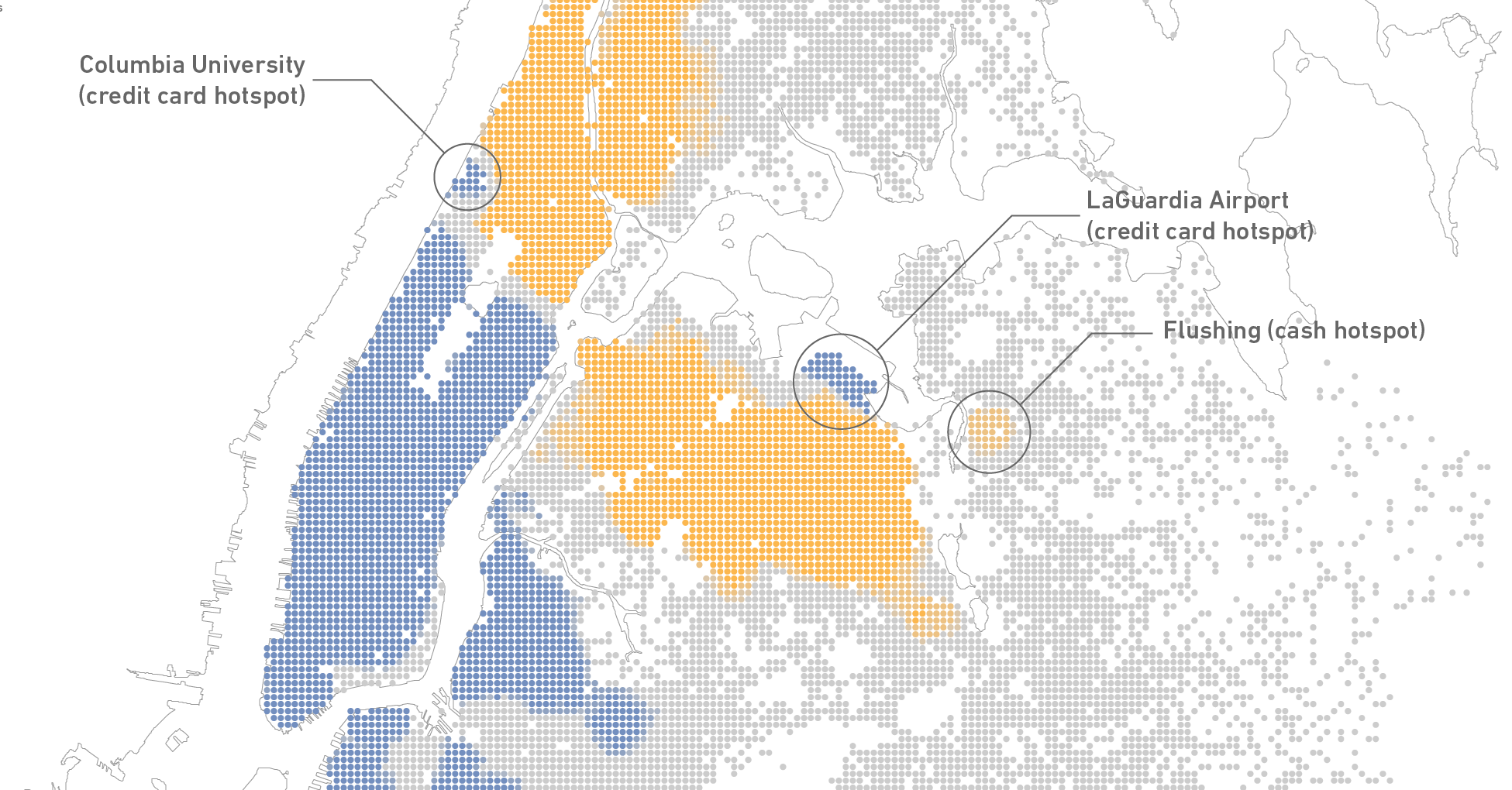

In all maps there are stark lines that demarcate where riders predominately use cash (shown in yellow) and where they use credit (shown in blue). The areas marked with yellow are the places where cash is king. With the exception of a credit card hotspot surrounding Columbia University in Morningside Heights Manhattan payment types divide cleanly along income lines, where wealthy neighborhoods flanking Central Park (the empty white rectangle in the middle of the map surrounded by blue to the south and yellow to the north) on the Upper West Side and Upper East Side pay for taxi trips mostly with credit cards and poorer neighborhoods to the north in Spanish and Central Harlem are dominated by cash. One interesting aspect is that the socio-demographic characteristics of neighborhoods seemingly play a large role in determining payment type. It is likely that the cash or credit choice is a function of access to a bank account, for which these spatial data are a good proxy. Another takeaway is that much of the city still does not produce a lot of taxi trips and there is not enough data to present primary payment types at all.