Personal Census Atlas

A visualization of the U.S. Census through the lens of one person’s longitudinal location data.

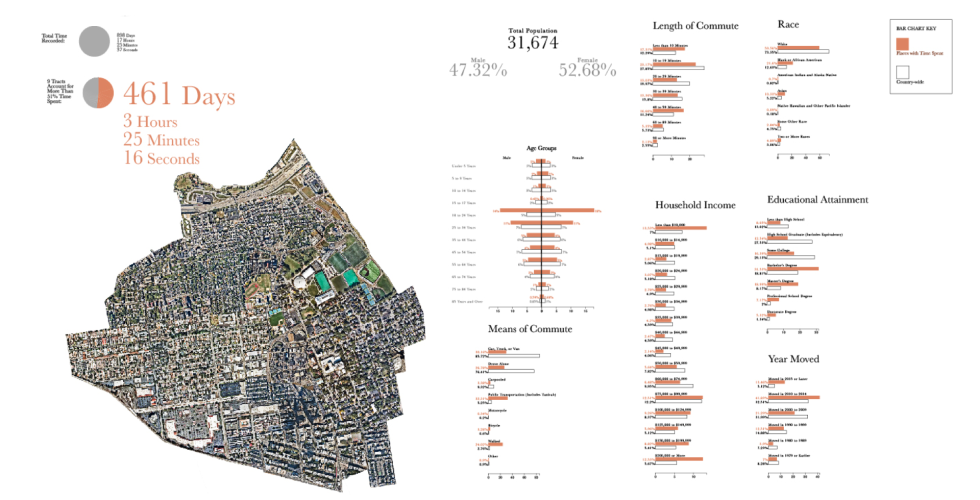

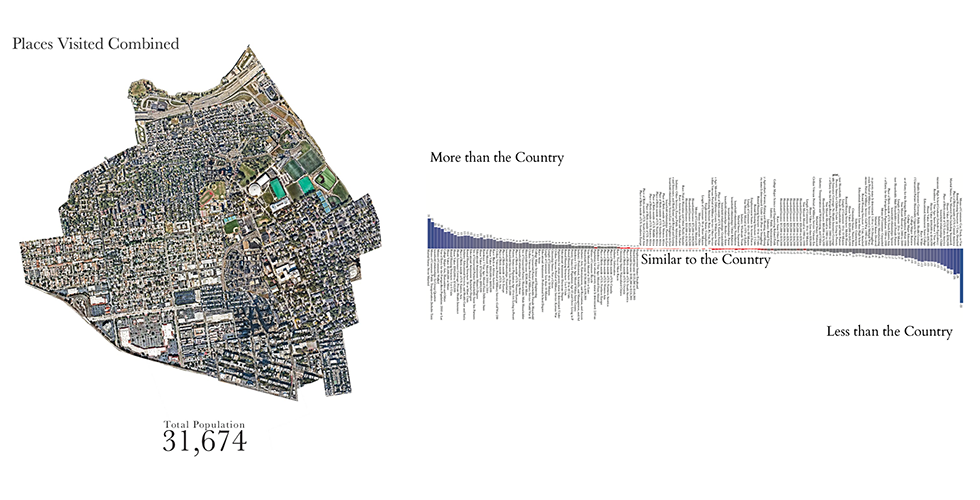

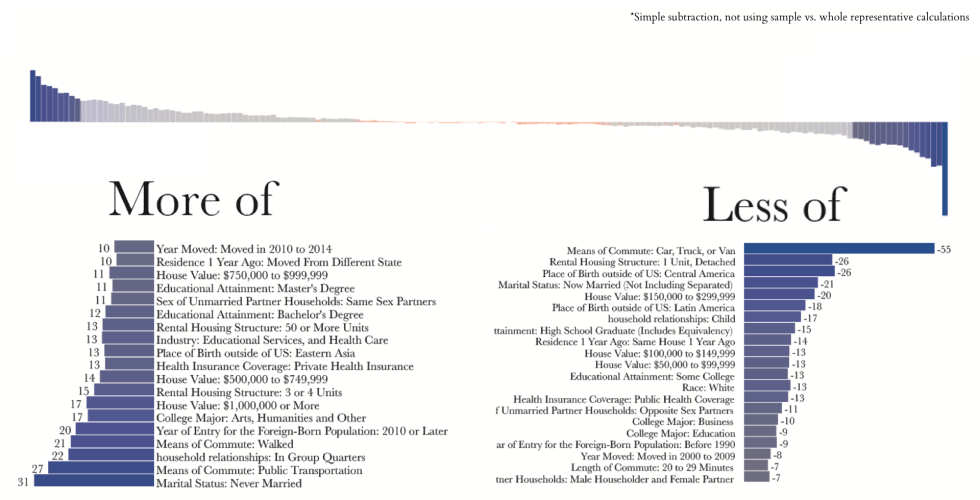

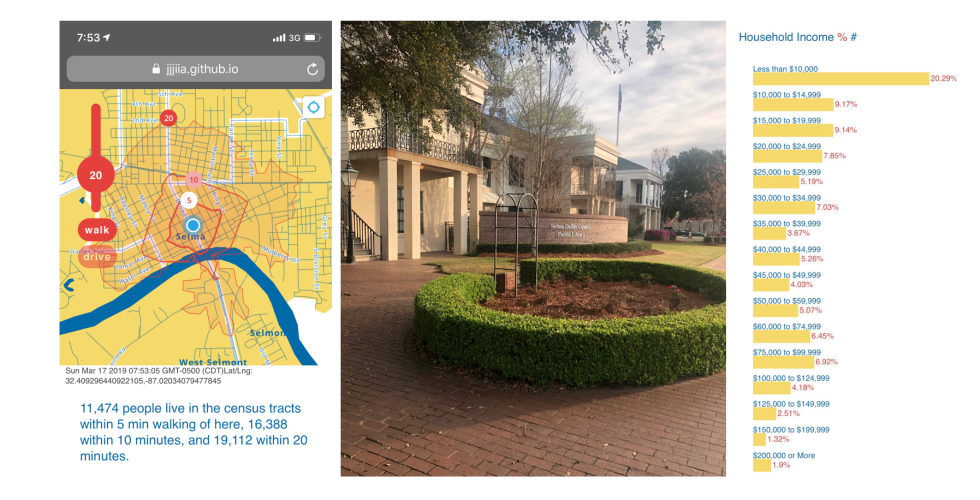

This project visualizes the U.S. Census through the lens of 1 person’s location data over the course of 3 years. It addresses the potential of self quantification in the personalization of public aggregate data. The dataset included 899 days of usable data, containing just over 21,000 records of time and location, most of which were in the United States. The over 20,000 American locations recorded are not all unique, they fell into 2633 unique census tracts. Of these tracts, over half of the recorded time was spent in just 9 census tracts. These 9 tracts have demographic characteristics in common in contrast to the rest of the country. The maps contained in this project presents these 9 tracts as a hypothetical island and displays the Census information for this combined area in the same style as a traditional census atlas.

Until 1970, the Census was conducted by a team of Census takers that visited each home and filled out Census forms by asking questions of the residents. However in 1970 the Census became self-enumerated, and when many Americans set a pen to the Census forms for the first time, some struggled to categorize themselves. For example, one of the questions that the form asked was “Relationship to Head of Household”. Because no option was given for husband of household, married women saw, for the first time, that they were not able to self-identify as the heads of their own households. In the subsequent Census of 1980, this option was changed. Amid all the other changes that usually occurred between one Census and another, the rewording of this category may seem like an insignificant detail. However, this is a good example that talks about the difference between how we are being counted and how we count ourselves. We are being counted all the time. Despite the increasing nuance and sophistication of classification and categorization systems, the formalization of categories is always going to be playing catch up to how we can define ourselves. Is it possible that we can challenge the transactional nature of our current relationship with data by viewing aggregate data through the lens of self knowledge?